In the September 2015 issue of New Power we asked industrywatchers how they thought this year’s Capacity Market auction would play out. Here’s what they said:

Prequalification for this second Capacity Market (CM) auction closed slightly later than planned, on 28 August. The resulting register, due for publication on 25 September, will give the first real indication of how much capacity could enter the auction, and of what type. But one thing we learned from the first auction in 2014 was that capacity able to enter the auction might offer little clue to what capacity leaves it with a contract, and at what price.

Given that uncertainty, can we speculate on what may affect the auction this year?

The low clearing price was the major surprise for most in last year’s auction. What drove that? Robin Cohen, vice president at Charles Rivers Associates (CRA), says it “can principally be explained by expectations of some reasonable price recovery in the energy market and the consequent determination of market participants to ‘hang on in there’, combined with substantial low-cost new entry.”

What factors could affect the price this year?

The headline addition to this year’s auction is the inclusion of interconnectors. But that addition was not seen as a “game-changer”, although it could add nearly 3GW to the capacity available.

“Interconnectors will almost certainly take any price that is available – so you would expect them to win contracts at the expense of generation”

Anthony Tricot, senior executive economic advisory at EY, said: “The participation of interconnectors is probably a red herring for the auction outcome. The interconnectors that exist now should be price takers, and for new ones the decision to invest will principally be made on the basis of the cap and floor regime.”

Ronan O’Regan, director and utilities consultant at PwC, noted that the potential interconnector capacity in the auction was higher than expected because National Grid had taken a slightly different approach in calculating derated capacity. He said interconnectors would “almost certainly take any price that is available – so you would expect them to win contracts at the expense of generation”.

Tricot also noted that despite government and regulatory push to increase interconnection, the CM was not being used to drive investment in new links. He said: “If government were serious about using the CM to determine which interconnectors get built, they would have made 15-year CM contracts available to them.”

Cohen compared the likely plant closures with the incoming interconnectors, saying: “The overall balance of supply/demand does not appear to have changed much,” with 2.9GW of interconnector capacity offsetting the impact of 2.5GW plant closures.

Some large plants will certainly close soon – E.On recently confirmed the closure of Killingholme, for example. But O’Regan noted that in most cases these were plants that were unsuccessful in the first auction, so “this shouldn’t directly affect the price this time round”.

The closure of Scottish Power’s Longannet plant is another matter. O’Regan said its loss would “increase the target level of capacity to be procured and therefore should all things be equal lead to a higher price”. Although it did not enter the 2014 auction it suggested it would be available in 2018/19.

Tricot also noted that the decision to close would affect the T-1 auction for that year: “It is one of the biggest coal plants in Europe, at 2.4GW, and … it could more than double the amount to be bought at the T-1 auction for 2018/19.”

Altering the balance

There are relatively few new large plants that are likely to enter this year’s auction for the first time, apart from Watt Power’s two 300MW open cycle gas turbines (OCGTs). But the equation has changed slightly for some plants that did take part last year.

ESB’s 900MW Carrington plant is one to watch. This may be the plant’s last opportunity to secure a 15-year agreement as new-build. O’Regan said: “Whether they will go for a long-term contract or a one-year agreement in the forthcoming auction will depend on price. But either way, they will add further competitive pressure.”

“If [existing plants] have already contracted in 2018/19 they only need to factor in incremental losses to their 2019/20 bid”

Other factors that may affect the bids from existing plant include the outcome of last year’s auction. EY’s Tricot noted: “Last year, existing plant may have factored in several years of losses [before the delivery year]. If they have already contracted in 2018/19 they only need to factor in incremental losses to their 2019/20 bid.”

Some other broader issues affecting this year’s auction were listed by Simon Hobday, energy partner at international legal firm Osborne Clarke.

He said uncertainty around the reliability of ageing nuclear and conventional plant fleets could put upward pressure on prices. Another important factor was the changing subsidy framework for renewables.

Changes in the Renewables Obligation and other subsidy regimes are driving a boom in investment to beat new deadlines, but thereafter investment is likely to slow.

Renewables with subsidy cannot offer capacity to the auction, but the shift in the UK’s portfolio may be significant. Tricot said the effects are uncertain: “Two factors operate in different directions. If there is less low-carbon we will need more conventional plant, which could push the capacity price up. But reduced intermittency could also lead to wholesale power prices being higher and less volatile, making it more attractive for thermal plant to sell into the energy market.”

Hobday also named some factors that could put downward pressure on prices, including low gas and coal prices, lower demand, and the participation of plant that “is fully amortised and sitting there, to get a few more years of use out of it”.

CRA’s Cohen also noted similar factors: “Price expectations may well have taken a knock: the clean dark spread on forwards instead of recovering has fallen further… These falling energy margins in addition to expectations of a tighter supply of [emissions allowances] in the long term could then lead to marginal generators bidding higher than in the last auction.” But he added: “At the same time, increased supply of additional low-cost new entry could pre-empt any significant overall price recovery.”

For Tim Emrich, chief executive of UK Power Reserve, the extra capacity likely to participate in this year’s auction was the overriding factor. With more distributed generation, interconnectors, several new large gas plants and some capacity that did not enter last year, “there is a massive surplus”, he said, “and it’s a buyer’s market for the government”.

“There is a massive surplus and it’s a buyer’s market for the government”

He was sure the auction would clear at a lower price than last year and speculated that it could be as low as £10/kW. In that case, he said, the only new-build that would take 15-year contracts “would be diesel”; large gas plants would ask whether it was worth taking a 15-year contract.

Looking further out

For Tricot, looking forward, delivery is the biggest uncertainty. He asked: “How much new-build and opt-out plant will really be in place in 2018/19, since the financial incentives to deliver on their position in the auction may be limited?”

Looking further than this year’s auction, O’Regan considered that “it might take a few years” for prices to rise, but he expected a lift in the medium term, because the old coal plants that won contracts last year (around 9GW) “should begin to drop off the system in the early 2020s to be replaced by new CCGTs [combined cycle gas turbines]”. Those plants would need £35-40/kW and that “should mean prices in the CM should rise to something like the government’s original estimate”.

“How much new build and opt-out plant will really be in place in 2018/19, since the financial incentives to deliver on their position in the auction may be limited?”

O’Regan said although the Trafford CCGT did accept a price of £19.40/kW last year, “there is a fair amount of scepticism about whether that can be replicated (or indeed whether the Trafford project will even get built)”.

For Hobday, the concern looking forward was how little was clear yet from the new government about its policy framework. It had made specific announcements (eg reducing or restricting the scope of subsidy support for onshore wind and solar), but had not provided a new narrative.

He said there was uncertainty about the overall policy framework and market incentives. As a result, there was uncertainty as to the position of the Capacity Market in the future energy market, and about how both the auctions, and final delivery, would play out. Hobday said: “We have people trying to make a decision now for investments in a market in four to five years’ time, when all we know now is that the government are conducting a review or ‘pause for reflection’ on the market and we won’t know until the autumn at the earliest what it looks like.”

Emily Agus, senior development and environmental engineer at Ramboll, warned that the system would be less secure. She noted that existing generation and interconnectors will make up the majority of the capacity awarded, with the remainder of the necessary capacity made up of smaller peaking plants with lower capital costs. She said: “In the short term, this is likely to ensure security. However, as the larger plants begin to close, they would no longer be able to provide baseload capacity, meaning that in the medium to long terms, with no larger plants being replaced, the smaller units would be expected to run for longer hours.” She also noted that location was another important aspect of security.

The CM and the trilemma

The government has claimed the Capacity Market as a success, citing the low price at which the 2014

auction cleared. But others raise questions over whether the CM is too limited, and does not properly reflect our broader energy aims.

Agus summarised that broad issue: “Is it possible for the generation mix to be secure, low-carbon and low-cost all at the same time?”

She said the UK’s legal obligations to reduce carbon emissions and keep the lights on were “very likely to mean an increase in electricity prices – at least in the short term. And, the longer investment is delayed, the higher prices are likely to be”.

Hobday considered that there had been too little attention paid to the demand side and how it could participate on an equal basis.

“Government doesn’t seem to understand that in process plant the process is king, not the power

production. It has seriously disincentivised manufacturing and process industries from getting involved [in the way it has structured the market].” The CM “appears loaded against demand response, and I don’t see any drive to remove the underlying fundamental difference in how they [generation and demand response] are treated.”

“The market appears loaded against demand response”

George Grant, managing director at Stag Energy, raised concerns over the fact that the CM does not differentiate between plant with differing CO2 emissions, or favour plant with flexibility to offer a system that needs it more and more.

However, he was not advocating major changes to the CM framework at this stage, saying: “It would seriously undermine investor confidence if Decc were to instigate a major overhaul of the CM before it has even begun to operate.”

Nevertheless, Grant said: “Some attention may be warranted to address CO2 emission implications or the ability for plant to provide rapid response in order to enable National Grid to effectively manage the system.”

And the long view:

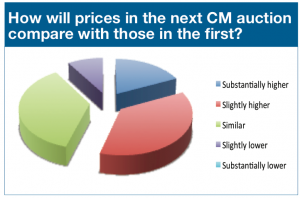

In March 2015, soon after the first CM auction, New Power asked readers how they thought the price might change in the second. Few thought it would rise:

Subscribers: login to the archive to read more analysis.

Not a subscriber? Email [email protected] for details