Mark Howitt argues that the government’s measures are failing to provide secure power over the long term

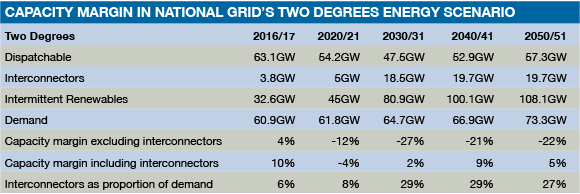

National Grid’s 2017 Future Energy Scenarios, which set out four ways energy could evolve to 2050, only has one scenario – Two Degrees – in which dispatchable generation and interconnectors provide a positive capacity margin in 2019-26. All the other scenarios have negative capacity margins from 2018/19 onwards. Even in Two Degrees the positive capacity margin is achieved by relying on imported electricity for 30% of peak demand, which is unreliable and unrealistic – even more so after Brexit.

Investment is not directed towards solving the problem at the right scale. Instead investors are heading towards small-scale, partial and sometimes inappropriate solutions to large-scale problems. This disconnect is getting worse and will continue to do so.

National Grid is ignoring factors that make the problem even bigger. Its figures for peak demand largely ignore electrification of transport and heating, which would increase demand up to fivefold. This conversion to electricity will also have unpredictable effects on the daily profile.

In Two Degrees, all cars and most heating are converted from fossil fuels to electricity. Currently each of these consume a similar amount of energy to today’s total electricity consumption, yet although these two conversions would appear to triple the demands on the energy network, the scenario only envisages a 20% increase in peak demand.

The scenario assumes that economic growth is balanced by increasing efficiency, without accommodating the ever-increasing gadgetisation of society. This is largely unpredictable: mobile phones and handheld computers have grown from nothing to immense in just one decade. And it relies on a proportion of intermittent generation to provide for both actual peak demand and the required generation margin.

The government and National Grid expect that the lack of large-scale domestic capacity will be addressed by an increasing number and size of interconnectors, reaching 20GW by 2050. Interconnectors are an important part of the solution, but we cannot rely on them to deliver energy cost-effectively at all times that we need it. They are expensive, and because they outsource the country’s electricity generation to neighbouring countries, that option compromises Britain’s security of supply.

Where will power come from?

By 2050, in the Two Degrees scenario, National Grid expects that MW-scale storage will deliver 9.7GW, carbon capture and storage will deliver a further 14.5GW (this is 30% higher than in last year’s equivalent Gone Green scenario), interconnectors will deliver 19.7GW and nuclear power 3.7-7.3GW. All these are at best uncertain. But even National Grid’s assumption leaves a gap in electricity supply of 63.9GW – fully 87% of the 73.3GW total demand.

There is an urgent need for more dispatchable power by 2025. In two scenarios the need is for 10-15GW; in the others it is as high as 20-25GW.

One option to fulfill this need is new generation. But if that is gas-fired, we would be in breach of international treaty and moral obligations. If the load factors on these power stations average well below 30%, as is likely, continued subsidies would be needed.

The answer is better use of our assets. The Two Degrees scenario includes 108.1GW of predictable but not dispatchable renewable generation (such as wind power). For long winter periods, wind generation remains on average above 30GW, but is highly fluctuating. Storage will allow us to meet our emissions obligations by enabling us to make full use of this renewable generation – but only if the storage has sufficient duration at the rated capacity to deliver energy for the entire peak demand period for which renewables may not generate (five hours or more). Batteries cannot provide in that scale or that duration. While they help greatly with grid balancing and ancillary services, they cannot provide dispatchable back-up to renewables. Large scale storage is necessary.

Such large-scale storage is available (our solution uses compressed air) but is capital intensive. Instead, what is required is some strategic thinking from government and industry. It can be built and operated profitably in today’s markets without direct subsidy, but it needs:

– A long-term contract (15 years) for energy – which would also deliver cheaper electricity over the term than a succession of one and two-year contracts.

– Support for the construction of a first-of-a-kind plant of each large-scale technology (in our case sized at around 40MW/200MWh).

– Phasing out of subsidies to fossil fuel generators – the Capacity Market.

More broadly, we need a market design that is based around renewable generation and storage, with some nuclear baseload; and one that is, crucially, simpler. Adding “patches” in the form of new contracts and rules on an ad-hoc basis is more expensive and less investable for all participants.

Mark Howitt

Director

Storelectric