UK pension funds are looking for investments in green energy, Doug McMurdo, chair of the Local Authority Pension Find Forum, told a fringe meeting at the Conservative Party conference. He told the audience that with £250 billion under management by his LAPFF members: “We are big in institutional investment. We can help. Our door is open”.

His call came as new legislation on UK pension funds takes effect: from 1 October, pension scheme trustees must take account of climate change risk in their investment decisions.

By that date they must have updated their Statement of Investment Principles (SIP) to include climate change as a material consideration with financial implications. The Pension Regulator’s new investment guidance for defined benefit schemes states that trustees should understand the implications of the systemic risk of climate change on investment decisions.

In a blog about the change, Field Fisher’s Michael Calvert said, “Where scheme assets are invested in pooled funds, trustees may feel that there is little they can do to influence the approach of either the fund manager or investee companies to climate change or wider environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues. This is unduly pessimistic, and leaves trustees exposed to a disproportionate drag on investment returns as other schemes align their strategies with best ESG practice.”

Tim Smith, of Herbert Smith Freehills, said “Some trustees may be tempted to see this merely as a tick box exercise. However, trustees need to consider how they can demonstrate that they are taking ESG factors seriously, as the risks associated with paying lip service to them are increasing.”

In the October 2017 issue of New Power Report we examined local authorities’ progress in investing in green projects. Read the full article:

Investment: Can we square the virtuous circle?

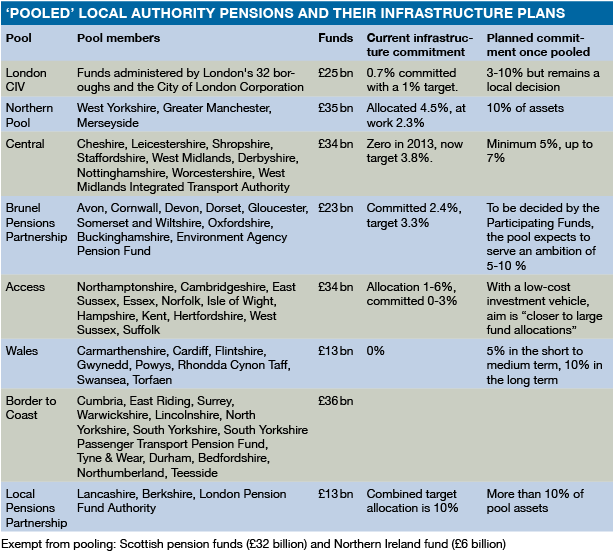

Local authorities will be ‘pooled’ and preparing to make major investments in April 2018 – just as developers are expected to be selling projects and recycling capital. Janet Wood asks whether UK investment can join up with UK infrastructure at last

Large public pension plans from Canada, Australia and other countries are major investors in UK infrastructure. That has raised a question: where are the UK pension funds? A “virtuous circle” in which UK investors fund networks, new generation and other energy assets – and reap the returns over decades – is attractive financially and politically. Why has it not happened?

Local authority pension funds are a good example. Each is independent and that means that although they may have billions of pounds under management, they are small funds. Investments have to be diverse and so may be relatively small – £10 million or £20 million for each – and that means administration, due diligence and other deal costs have to be rock bottom to ensure the investment makes the necessary return. They have to fit tight investment criteria and pension trustees have fiduciary duties that require them to be cautious investors. But projects in the new energy economy cannot rely on easily packaged projects and rafts of in-service data to help ease costs and lower risk.

The size issue is well-known and is being tackled in two ways. One is to pool local authority pension investments. The other is to offer a dedicated fund designed to meet public sector pension needs. This is the Pensions Infrastructure Platform. It was launched with fanfare and New Power has spoken with a representative (see interview). But the PIP has frustrated some and progress in making investments has been slow.

Come together

Kieran Quinn is chair of Greater Manchester Pension Fund. He says: “I don’t think local government pension schemes are anywhere near where the government wants them to be on infrastructure. There are likely to be questions asked and prods from DCLUG about how local government schemes are approaching this.”

He sees pressure to invest not just because the funds are looking for projects but, more widely, because the country needs investment in infrastructure. “There are issues around energy creation and distribution. A couple of years ago we were within six hours of running out of energy for the country and clearly it is a concern for government,” he says. Before talking about how the funds are responding, he notes: “If we are talking about bringing new sources to bear then we can help, but it starts with government. Its policy is unclear.”

But, he admits: “It’s also about a lack of expertise in the government pensions world.” Initially government wanted pension funds to merge, but now, Quinn says: “We are pooling instead of merging, I guess because of the potential impact on the local authority pension scheme world over the next three to five years. Pooling was seen as a better way first to avoid fees and then to widen opportunities.”

Quinn’s fund, Greater Manchester, has successfully invested in infrastructure, but he is clearly excited about the opportunities for a pooled fund. He says it will be fundamentally different, because “we want it to have a much more direct holding, a direct approach, and that is different for a uk pension fund”. He adds that, in energy, “all pension funds are going through a transition away from fossil investments”. “But in future we are looking at larger projects, direct investment and a place on the board – the type of thing that the large Australian and Canadian pension funds have been doing for decades.”

He stresses that this is the start of that journey, and the pooled funds remain relatively small. However, he says: “I think the ability to do more, be more direct, seek out larger opportunities, is one of the first steps new pools will be taking.”

The pools are now set, although at different stages of realisation, and are expected to begin work in April next year. Quinn notes that: “There is still quite a complex process to go through. There is no guidebook on how you approach it. Some funds are starting the transfer to pools, some won’t start until after April. It depends on governance and prioritisation.

The pools are now set, although at different stages of realisation, and are expected to begin work in April next year. Quinn notes that: “There is still quite a complex process to go through. There is no guidebook on how you approach it. Some funds are starting the transfer to pools, some won’t start until after April. It depends on governance and prioritisation.

“Clearly we want to transfer asset oversight, but ownership will remain with the funds,” he says. “Pools will act more like an asset manager,” but that covered a variety of approaches.

Part of the variation is about reducing administration costs: funds will process that transfer to pools at a time of least cost, starting with the most liquid assets. The total valuation of funds is about £250 billion, and “when the government produced guidance two and a half years ago they acknowledged that it would be easier to move liquid assets – but there is no guidebook”.

Investors want policy certainty

Greater Manchester and its partners started early. “GLIL has been working for nearly four years and we have taken direct holdings in a couple of energy initiatives,” says Quinn.

He foresees an active market after April, when “rather than focusing on assets we have, it is in the area of new projects that we will see decisions being made”. “Everyone is concerned about their fossil fuel holdings and what to do about that,” he adds, “and we all want to increase electricity production by renewables.”

The difference from April will be that “lots of funds were talking about £20-40 million as the opportunity size and when the pools start to come together they will be looking for £60-100 million”. Quinn thinks “that will be a game changer”.

“In three or four years time… That’s where I see the big difference. Under £30 million there are still quite a few opportunities out there, but it is the much larger schemes that haven’t really come forward in a sustainable investment way.”

Quinn reiterates his frustration with a lack of long-term policy that would give stable investment options to funds.

“Government has been moving out of supporting green and renewables for the past six or seven years. That has brought fewer opportunities and less certainty,” he says.

At Greater Manchester, “we have been talking about large-scale opportunities for a while”. GLIL has invested £60 million in a biogas project, and has a stake in the Strathclyde wind farm – both as part of GLIL and independently. Quinn is looking for a return of CPI plus 3% – the “sweet spot” is normally 6-7%. But it does go higher or lower and the fund can vary its risk level.

In fact, he says: “We are looking at taking more development risk, we are prepared to expand our risk profile. With very low returns from government money we are looking elsewhere. There is a blended opportunity if you take some development risk.” Some pension funds “are looking to blend it so you get a guaranteed return on the entity as a whole,” says Quinn. “You price the whole opportunity at 5%, but 10% of that might be development risk with an 18% return. These conversations are taking place. It’s where the more mature funds are looking.”

In fact, he says: “We are looking at taking more development risk, we are prepared to expand our risk profile. With very low returns from government money we are looking elsewhere. There is a blended opportunity if you take some development risk.” Some pension funds “are looking to blend it so you get a guaranteed return on the entity as a whole,” says Quinn. “You price the whole opportunity at 5%, but 10% of that might be development risk with an 18% return. These conversations are taking place. It’s where the more mature funds are looking.”

I ask about whether storage fits the funds’ risk profile yet. Quinn says: “I have had storage conversations in the past six months directly, and been aware of it for the past 12-18 months. It’s a new area to look at – we are not in the vanguard, where I would like us to be, but we are having those conversations.” When we speak, Greater Manchester is looking at a storage opportunity, bit Quinn says: “We may find we come back to it in five years’ time when the costs are higher but the returns are more certain. The hardest part about doing due diligence is how you price unknowns, and in the storage area there are still a lot of unknowns.”

Riding the wave?

I suggest that this is good timing for pension funds to acquire generation projects, because developers are looking to recycle their capital from the construction boom of the past few years. Quinn agrees: “Anecdotally I am hearing that, and so are my advisers. Will the sector be able to take advantage? I believe and hope it will.”

But he warns: “Some of the pricing of these assets is quite high because there is a lot of capital that wants to come in. We can add Chinese investors to the Canadians and Australians. Sometimes the bidding wars on these make the pricing… I won’t say unrealistic, but it is challenging, definitely.”

What do funds need from their advisers and analysts at this point? Quinn says: “We need schemes to come forward. Lots of funds still prefer to invest indirectly in funds of funds and that will continue for some time. We would sign up to a £10 million scheme tomorrow if the returns were right, but we’d rather have one £60 million scheme than ten £6 million schemes because of the cost – we have to do due diligence on each.”

The Pensions Infrastructure Platform (PIP) has been in operation for a few years and was intended to ease funds’ investment into the sector. Has it been overtaken by the pooling process?

Quinn says: “There is resistance to PIP. They think it’s too costly and the returns are not in the region that [funds are] looking for. But that doesn’t mean that there are not opportunities in PIP that hit the sweet spot.”