Janet Wood explores some of the issues the GB power industry has to consider in its future as a third party connected to the EU’s Internal Energy Market

After the Brexit referendum the fear was expressed that electricity imports to the UK from its neighbours would be interrupted. That fear receded. But of more practical importance to the UK outside the EU are issues to be managed from buying (and importing) spare parts to buying the cheapest power. It all adds up to more uncertainty and a need to work harder to maintain resilience.

Big is better

As a part of the EU’s internal electricity and gas markets, the UK has been able to take advantage of access to a much larger system.

As a ‘third country’ the UK now takes no part in decision-making for that market and there is a more remote relationship between the GB electricity market and that of the EU. Although it is not clear yet exactly what all the implications will be, that change in relationship is likely to decrease GB resilience.

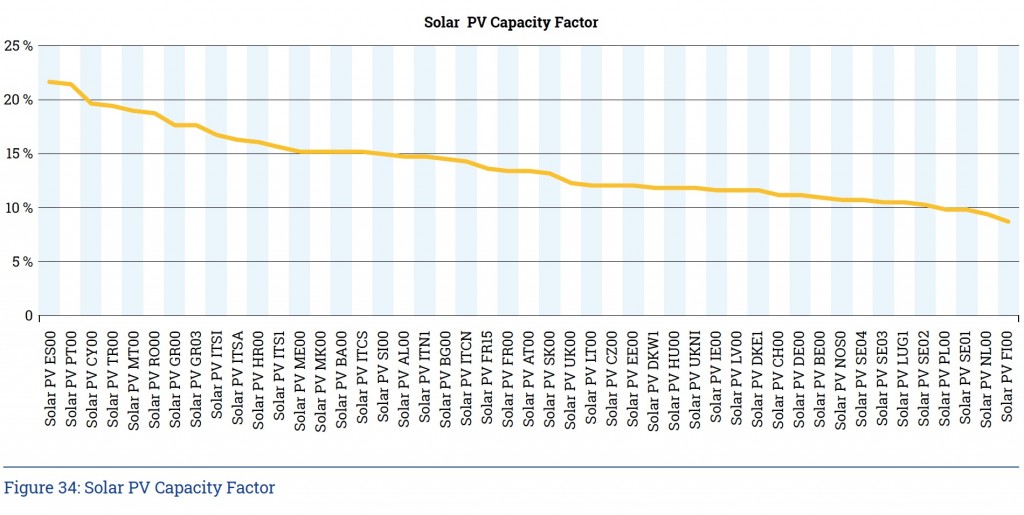

First, being in a larger market gives the UK access to the cheapest power options. A joint report from European gas and electricity network bodies Entso-e and Entso-g illustrates this. PV capacity factors in Spain rank close to 22%, the bodies say in their forward-looking Ten Year Network Development Plans, while in the UK the capacity factor is closer to 15%.

Source, ENTSOE TYNDP

The authors note: “Solar PV is generally most competitive in Southern Europe, whereas onshore wind is particularly competitive in Northern and Western Europe. For offshore wind, the lowest costs take place in North Sea and southern Baltic Sea regions”.

The larger market provides more opportunities to reduce cost by taking advantage of specific characteristics of different market participants. Hydro power in Norway, for example, provides flexibility across northern Europe with benefits on both sides. Countries with large wind portfolios can import power from Norway when wind is low. But equally important, Norway can preserve water levels in its reservoirs – which are mostly filled annually by snowmelt – by importing cheap power when wind is abundant.

Importantly, a larger system may also provide a market opportunity for forms of generation that are needed for other reasons. For example, most electricity systems need power plant with rotating machinery to provide stability and help ‘ride through’ faults such as frequency or voltage excursions.

GB’s National Grid ESO, among others, is working on new ways to meet this need, but until new options are firmly in place, inertia providers like gas turbines are required on occasion. At the same time, the economic basis on which these plant operate is being eroded by renewables. The grid services provided by, for example, gas turbines, will be extremely expensive unless the gas turbine can stack other revenues.

The TYNDP says, “investment in new conventional forms of energy such as nuclear and CCGTs with CCS are difficult due to the high CAPEX and the need for high operational hours” which it estimates at 60-70% for new gas CCGTs and 80-85% for new CCGTs with CCS and nuclear power plants. The UK’s existing gas turbines, in contrast, have been operating for many years at 20-30% of potential hours and many have closed as a result.

But a larger energy market means more potential customers for energy sales. So it is possible that gas plant may make some sales into European markets to add to those in the GB market. It has to be said that this cuts both ways: European generators can sell here, and UK gas turbines operators complain that European suppliers are able to undercut them because of unfair network charges.

But from a ‘whole of market’ perspective it raises the possibility that the system can be more efficient: it can provide the necessary grid services at lower cost, because fewer conventional plants have to be supported.

Short term shocks

The UK’s resilience against near term shocks has been reduced. Access to the larger system gives the system operator more tools to manage supply and demand close to dispatch.

The importance of this tool has been illustrated this summer, as NGESO struggled to maintain stability in a situation where demand was reduced by up to 20%, due to the Covid-19 lockdown, while supply from GB’s renewable energy sources continued to increase.

That situation left the system short of inertia. It meant NGESO had to dispose of some power so it could bring additional gas turbines – pushed out of the merit order by abundant renewable supply and depressed prices – into operation. To achieve that, NGESO acted in the market to force power exports (as well as other actions, like turning down wind and paying to pump water up at GB’s own pumped storage hydro plants).

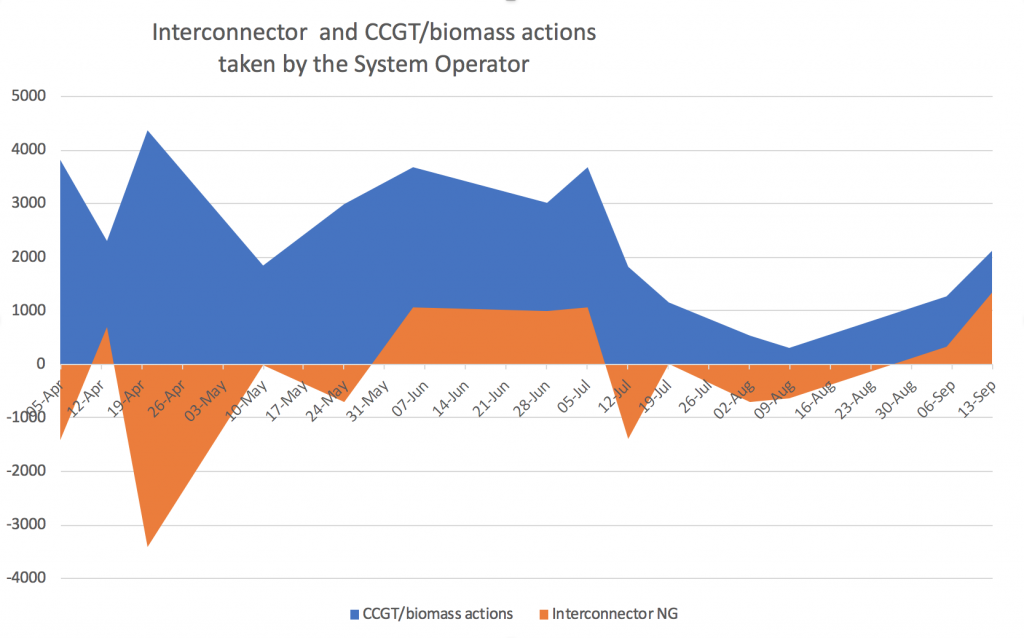

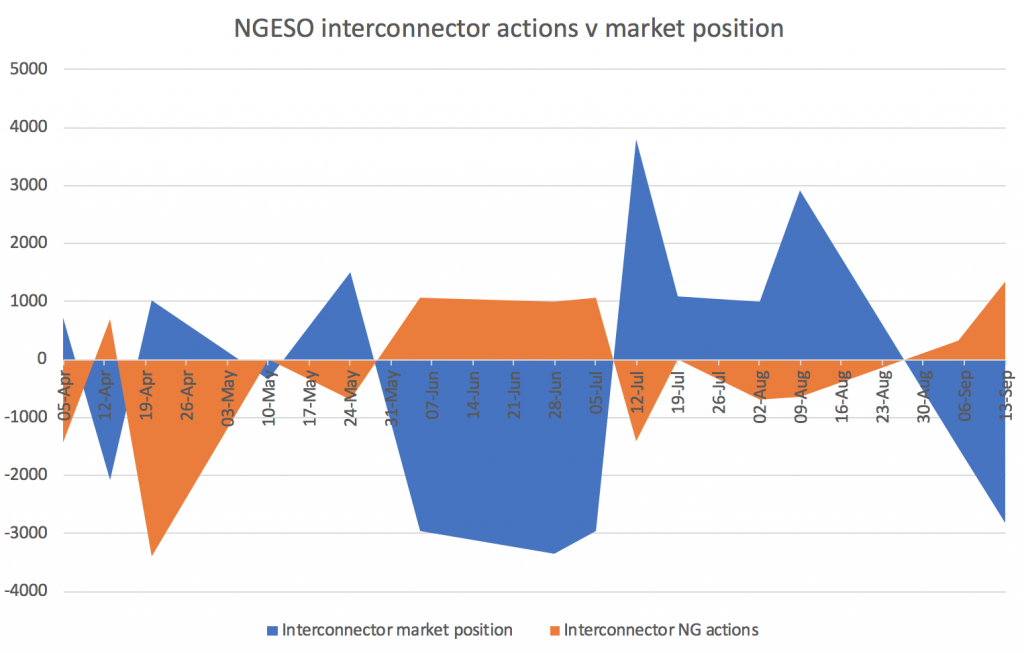

the system operator has used trades across the interconnectors to provide ‘headroom’ between supply and demand

The charts show how the system operator has used trades across the interconnectors to provide ‘headroom’ between supply and demand so it can recruit more thermal generators to provide frequency and voltage control, and how that compares with actions taken with regard to thermal plant.

It shows a series of snapshots of trading periods over the summer period, as highlighted by the system operator in its weekly update providing transparency on the control room’s actions.

Regulator Ofgem is consulting on the cost of those actions and clearly the Covid-19 summer has been a special case.

The graph above, showing NGESO’s near-term trades in comparison to the market position, makes clear the importance of access to our neighbours across the Channel during the Covid summer – an experience that NGESO suggested had important lessons for its plan to manage the GB system as levels of renewable generation increase dramatically over the coming years. Key to that, it reiterated in this year’s Network Options Assessment is at least a doubling in links with neighbouring markets.

Brexit will not mean that the interconnectors will no longer be available to GB traders and NGESO. But as a third country, GB traders will lose access to so-called ‘implicit’ trades which come complete with capacity booked on the interconnector.

As New Power has reported in the past, this leaves the UK with trades that are more costly, both because of higher administration costs and because they face bigger bid-offer spreads, and with less ability to make trades close to real time. In 2019 UKERC researchers Dr Joachim Geske, Professor Richard Green and Dr Iain Staffell of Imperial College estimated that this decoupling between the GB electricity market and the EU’s market could carry a penalty for GB of £270 million a year by 2030.

Near term response

The loss in being able to balance close to real time extends to managing reserve and response. This summer NGESO announced that plans for GB to join a new pan-European market for reserve power, the Trans-European RR Exchange (TERRE). When it began work on the new platform in February 2018, the system operator suggested it could meet 25% of the GB system’s balancing needs, in the process cutting GB balancing costs by €13 million a year.

The new market is designed to facilitate close to real-time (less than one hour) exchange. Generators with as little as 1MW of supply can participate in TERRE and so can smaller plant, via aggregators. Demand-side response providers can bid into the market on the same basis.In operation, the market works via system operators (SOs) in participating countries, that inform the Terre platform (known as Libre) of their reserve needs. The SOs then pass on offers of reserve from participants in their areas, which enter hourly auctions comprising four 15-minute periods (which can be linked). The Libra market platform manages the auction and returns the result to the system operators.

It became clear in 2019 that access to TERRE (originally planned for that year), would be delayed in the short term because UK participation depends on the readiness of the French system operator and is now not expected until 2021. Nevertheless potential UK participants, the system operator included, continued development of the necessary IT systems.

We have devoted a lot of time and resource into preparing for facilitating GB participation in the European RR market.

When the delay was confirmed on 4 September, NGESO said, “We have devoted a lot of time and resource into preparing for facilitating GB participation in the European RR market. We therefore share the disappointment of other stakeholders that it is now not possible to achieve this in 2020. We realise that the uncertainly will add more questions concerning the plan for GB Go-Live.”

But behind the immediate problem lay a bigger one: the UK’s position after Brexit.

Now that the UK is classified as a ‘third country’ and is outside the IEM it will not be able to join TERRE directly. The GB market now has to decide the way forward – whether to invest in a parallel platform, go it alone or find another way to interact with TERRE (see story here).

Other issues

These aspects of resilience within the electricity system are not the only issues to be considered. Many other aspects of resilience are equally important. Financial resilience is one example and companies fear that cutting loose from the EU will raise costs because of the increased uncertainty.

The UK’s largest domestic gas network Cadent, for example, noted in its response to Ofgem’s ‘draft determination’ on its income and expenditure plans, noted that “The uncertainty created by Brexit adds a premium to the return sought from investments in the UK” – this despite the fact that some would say that the entire future of gas distribution is in question and according to Cadent, “the most material factor that currently distinguishes the regulated networks is the risk that investors currently perceive to long-term revenue recovery in the gas industry.”

The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) agreed. It said in its provisional findings on spending plans for water companies that “the significant spending plans announced by the government might reasonably be expected to lead to an increase in interest rates, while the Brexit debate continues to provide uncertainty about the Bank of England’s future interest rate decisions.”

the Brexit debate continues to provide uncertainty about the Bank of England’s future interest rate decisions

The CMA also extended the uncertainty over Brexit to such issues as filling staff vacancies. In its water company finding it said it would apply true-up factors in assessing staffing costs, because “there is considerable forecasting uncertainty due to macroeconomic factors, including Brexit”, and “there are concerns over the use of ONS household projections. These concerns are further amplified by the forecasting uncertainty created by Brexit and COVID-19.”

A key example of the type of indirect issue that UK power companies must deal with after Brexit is import and export, not of power, but of hardware: equipment and components. This is important not just for the UK’s power sector manufacturers, but also for suppliers who want to offer an ‘energy service’ model that may include, for example, solar PV installation or other energy efficiency backfitting.

The UK’s supply chain has been trading without barriers with the EU for many years, the EU’s aim being that for UK companies the distance is the only difference beween a sub-supplier in France or Croatia and one in the UK. This has facilitated ‘just in time’ approaches to construction and maintenance. After 1 January that will no longer apply and there will be ‘hard’ borders with all the administration that implies. The government has been working on an IT system to manage customs declarations known as ‘SmartFreight’ but that remains in beta testing and a final version is not due to be released until spring 2021.

Despite well-publicised early problems, it is hard to assess the long term potential for delays or import barriers of necessary materials or equipment into the UK – or exports, for subsuppliers with customers elsewhere in the EU. That, like much else, remains to be seen.

Further reading

Eelpower finds Swiss infrastructure fund backer to build battery storage at scale, aims at 1GW