The NGESO’s annual Network Options Assessment (NOA), published in January, set new network investment in train, with a recommendation that 41 new-build options proceed, at a total cost of £13.9B. The recommendation would see £183M invested this year.

But the decision also highlighted the potentially uneasy relationship between the push from NGESO and regulator Ofgem to use more competition to deliver network upgrades, and the need to provide certainty for competitive providers and ensure consumers are not exposed to the risk of funding stranded assets.

Each year the NOA assesses proposed projects against NGESO’s suite of Future Energy Scenarios and assesses whether they should proceed, not start or be put ‘on hold’. NGESO assumes that delaying start reduces the likelihood of stranded investment and means customers do not invest ‘ahead of need’. In broad terms projects are given the ‘proceed’ advice if they are critical in all NGESO’s future scenarios – ie they are ‘no regrets’ for consumers.

Competitively awarded projects would proceed on a ‘twin track’ to this process and NGESO is consulting until 15 February on the detail for ‘early competition’ (which aims to give potential bidders more opportunity to be innovative).

A risk for new investors

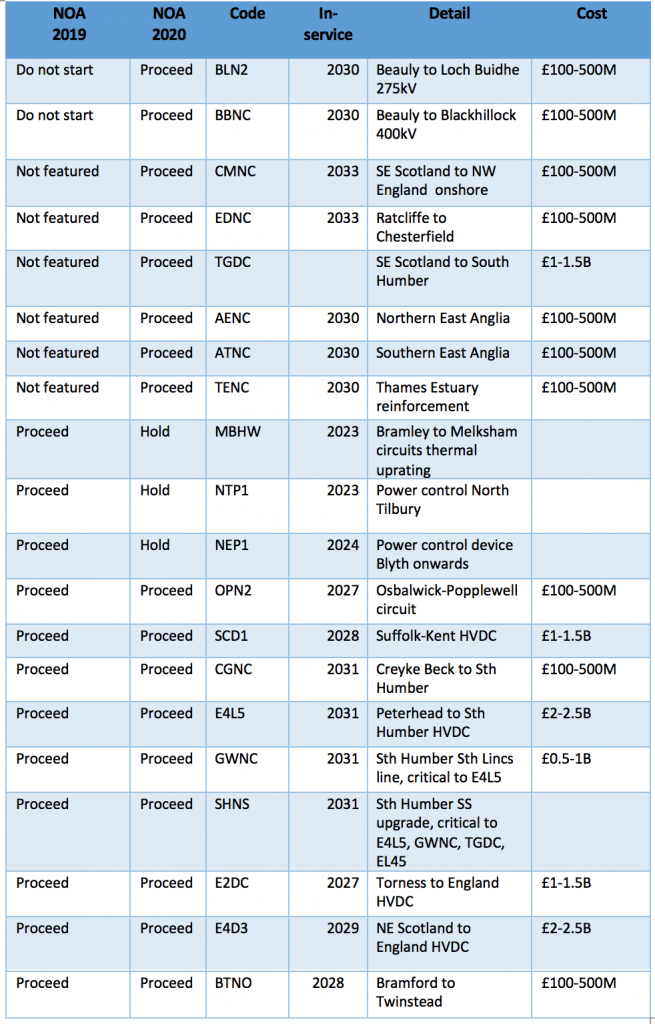

The table at bottom shows the 20 projects that NGESO identifies in its 2020 NOA as being potentially subject to competition – meeting Ofgem’s characteristics of being new, separable and of high value.

It is clear that there is a large potential ‘pipeline’ of contestable projects. That is important for potential new entrants: it not only suggests a long term industry with continuing work becoming available, but also the opportunity to reduce costs and innovate over time, both in engineering and in the associated costs such as running and entering the tender process.

However in the NOA, projects do not necessarily progress predictably from one category to another from year to year. Comparing this year’s assessment with last year’s shows some of the uncertainties inherent in moving to a competitive process. Only nine of the 20 projects have remained classified as ‘proceed’ across the two years.

Three projects have moved from the ‘proceed’ to ‘hold’ – despite originally aiming for in-service dates just two or three years ahead. Altering the timing on projects raises uncertainty and costs. That is a particular concern for potential new entrants who have to keep investors and contractors in play.

Meanwhile, six entirely new projects have been assessed to ‘proceed’, with some aiming to be in operation as early as 2030. That is a tall order for NGESO’s planned competitive process, which forsees a nine-year timetable from initial identification to project operation, with final investment decision late in year seven.

It remains a tight timetable even if the project listed is regarded as being ‘ready to begin pre-qualification’, which shortens the process by two years.

A risk for customers

Uncertainties in timing affect customers as well as investors. Continuing a project that would have been delayed in the NOA track means that customers bear the risk of investing ahead of need, or even paying for stranded assets. If a competitive process is slower at delivering an urgent new asset than would have been the case by using incumbents, other market participants who might have provided lower cost power or services will lose out – and so will consumers. Ofgem will decide on a case by case basis whether a specific project is a suitable candidate for competition. The judgement is a fine one.

Finally, if potentially half of projects are not assessed in the NOA but in a twin-track competitive process, overall visibility of the interdependent network is lost to potential network users and neighbouring networks. And there has to be a tight oversight of the parties involved, as the experience of Carillion shows.

Competition may bring fresh and valuable new thinking and reduced cost to the future development of networks, but adding competition to what has been moving towards a fairly flexible and responsive process has its dangers. The process will have to work alongside what will be a much ‘thinner’ NOA process.